The End of an Era? Why America’s Future Looks More Like 1914 Vienna Than 1956 Suez

The Slow Unraveling of a Superpower

Discussions about the decline of American global dominance are nothing new. For decades, analysts have debated whether the United States is on a path similar to that of previous empires. Often, the go-to historical parallel is the 1956 Suez Crisis—a single, humiliating event that starkly symbolized the end of the British Empire’s reign and the definitive passing of the torch to a new American hegemon.

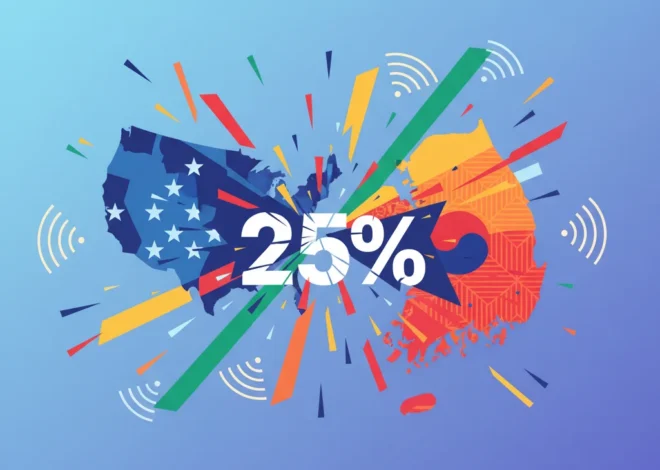

However, a more unsettling and perhaps more accurate analogy has been proposed. In a thought-provoking letter to the Financial Times, esteemed historian Dominic Lieven suggests we should be looking not at the sudden shock of Suez, but at the slow, systemic decay of Vienna in 1914. This comparison shifts the narrative from a singular moment of collapse to a protracted period of internal division, overstretched commitments, and a collective failure by elites to grasp the monumental shifts occurring around them. For investors, business leaders, and anyone involved in the global economy, understanding this distinction is not merely an academic exercise—it is crucial for navigating the turbulent decades ahead.

This post will delve into Lieven’s powerful analogy, exploring why the Vienna 1914 model offers a more fitting lens through which to view America’s current challenges. We will analyze the profound implications this has for global finance, the stock market, and long-term investing strategies in an increasingly multipolar world.

Suez 1956: The Myth of the Sudden Fall

To appreciate the gravity of the 1914 comparison, we must first understand why the 1956 Suez analogy, while popular, is ultimately misleading. The Suez Crisis was a watershed moment. When Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, Britain and France, in a secret pact with Israel, invaded to retake control. The venture was a military success but a geopolitical catastrophe.

The United States, led by President Eisenhower, refused to support the invasion and applied immense financial pressure, including threatening to sell off US reserves of the British pound sterling. The move would have collapsed the British economy. Within weeks, London and Paris were forced into a humiliating withdrawal. The message was clear: the world had a new master, and the old European empires were now secondary powers. As one British politician at the time lamented, “We have been subjected to a brutal and humiliating diktat by the United States.” (source)

The appeal of this analogy is its simplicity. It presents the end of an empire as a clear, dramatic event—a single geopolitical miscalculation that exposes the emperor’s new clothes. Many who predict America’s fall imagine a similar “Suez moment”—perhaps a failed military intervention, a dollar crisis, or a decisive technological leap by a rival that signals an unambiguous transfer of power. But the reality of America’s current situation is far more complex, gradual, and internally driven.

Ireland's Economic Juggernaut: Beyond the Headlines of a 12.5% Tax Rate

Vienna 1914: A More Ominous Parallel

Dominic Lieven argues that the pre-World War I Habsburg capital of Vienna provides a more sober and accurate mirror for the United States today. The Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1914 was not defeated in a single event; it crumbled from within, unable to manage its own internal contradictions while facing a changing external landscape. The world of 1914 was not unipolar but multipolar, with aging empires grappling with the rise of new powers like Germany.

Let’s examine the key parallels:

- Internal Political Paralysis: Pre-war Vienna was the capital of a vast, multi-ethnic empire torn apart by nationalist tensions and political infighting. The political elite were often more focused on internal squabbles than on addressing the existential threats looming on the horizon. Today, the US faces its own deep political polarization, with partisan gridlock often preventing consensus on critical long-term issues, from national debt to strategic industrial policy.

- Elite Complacency: The ruling classes of the old European empires were, for the most part, deeply complacent. They presided over an unprecedented era of globalization and technological progress and could not imagine that their world was on the brink of self-destruction. This mirrors a certain complacency in the West today, a belief that the fundamental structures of the post-1945 liberal international order are permanent, despite mounting evidence to the contrary.

- Overstretched Commitments: The great empires of 1914 were overstretched, maintaining vast global commitments that drained their resources and created vulnerabilities. The US today maintains a global military presence with security guarantees across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—a posture that is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain as domestic economic pressures grow and rivals challenge its influence in key regions. The US defense budget, for instance, is larger than the next 10 countries combined (source), yet its strategic focus is more divided than ever.

This comparison suggests that America’s primary threat is not a single external challenger who will deliver a knockout blow, but a slow, grinding process of internal decay that leaves it unable to adapt to a world that no longer plays by its rules.

The table below breaks down the key differences between the two historical analogies.

| Feature | Suez 1956 (British Empire) | Vienna 1914 (Empires) / Modern USA |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Decline | Sudden, decisive, and externally triggered. | Gradual, systemic, and driven by internal decay. |

| Key Trigger | A single, failed military/geopolitical event. | A “death by a thousand cuts”—political polarization, economic strain, and strategic overreach. |

| Global Power Structure | Bipolar (declining UK vs. rising US). Clear handover of power. | Multipolar. A complex web of rising and declining powers with no single successor. |

| Internal State | Relatively cohesive, but financially exhausted from war. | Deeply divided and politically paralyzed, making coherent strategy difficult. |

| Financial Implications | A currency crisis forced by a new hegemon, leading to a rapid loss of prestige. | A slow erosion of reserve currency status, fragmentation of global banking, and rising volatility. |

The Financial Fallout: Navigating a 1914 World

If we are indeed living through a “1914 moment,” what does this mean for the world of finance, trading, and investment? The implications are profound and demand a fundamental rethinking of risk.

1. The Fragmentation of the Global Economy

The pre-1914 era was the first great age of globalization, a period of free-flowing capital, trade, and migration, all underwritten by the British pound and the Royal Navy. That world was shattered by the war. A similar fragmentation is underway today. The era of hyper-globalization, championed by the US, is giving way to a world of competing economic blocs, “friend-shoring,” and technological decoupling. For businesses, this means supply chains are no longer just a matter of efficiency but of national security. For the global economy, it means slower growth, persistent inflation, and increased friction in international trade.

India's Tax Earthquake: Supreme Court Ruling Shakes Foreign Investment Landscape

2. The Challenge to the Dollar and the Banking System

A multipolar world is unlikely to remain a unipolar currency world indefinitely. The US dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” as the world’s primary reserve currency is being subtly but steadily challenged. The weaponization of the dollar through sanctions against countries like Russia and Iran has accelerated efforts by nations like China, Russia, and the BRICS bloc to create alternative systems for cross-border payments. According to the IMF, the dollar’s share of global foreign exchange reserves has fallen from over 71% in 1999 to around 59% in 2023 (source). While no single currency is ready to replace the dollar, we are moving toward a multi-currency system, which will have massive implications for banking, international debt, and the pricing of global commodities.

3. A New Paradigm for the Stock Market and Investing

For decades, the core tenet of successful investing was to bet on continued American-led globalization. A 1914-style world turns this on its head. Geopolitical risk is no longer a tail risk but a central factor in asset allocation. Investors will need to:

- Diversify Geopolitically: This means more than just buying international ETFs. It requires a nuanced understanding of regional power dynamics and identifying markets that may be insulated from or even benefit from great-power competition.

- Hedge Against Instability: Assets that perform well in times of uncertainty and de-globalization, such as gold, commodities, and real assets, may become more critical components of a balanced portfolio.

- Focus on Resilience: Companies with resilient supply chains, strong balance sheets, and pricing power in an inflationary environment will be the new blue chips. The old models of just-in-time manufacturing and global arbitrage are becoming liabilities.

The Gen Z Investor: Misunderstood Gambler or Disciplined Strategist?

Conclusion: History Doesn’t Repeat, But It Rhymes

The comparison of the modern United States to Vienna in 1914 is not a prediction of doom, but a call for humility and historical perspective. It warns that the greatest threats to a superpower often come not from a dramatic external blow, but from a slow, internal hollowing out. The Suez 1956 analogy offers a clean, simple narrative of decline. The Vienna 1914 analogy forces us to confront a messier, more complex, and far more dangerous reality—one defined by political paralysis, elite complacency, and a systemic failure to adapt.

For those in the world of economics and finance, this historical lens is invaluable. It suggests that the coming years will be defined not by a singular crisis, but by persistent volatility, the reordering of global supply chains, and a fundamental shift in the underpinnings of the international financial system. Navigating this new landscape requires moving beyond the assumptions of the post-Cold War era and recognizing that we have entered a new, more contentious chapter of history. The empires of 1914 sleepwalked into a catastrophe they couldn’t imagine. Our challenge is to face the shifting realities of our time with our eyes wide open.