The Whale in the Portfolio: A 19th-Century Lesson on Stranded Assets and the Modern Energy Transition

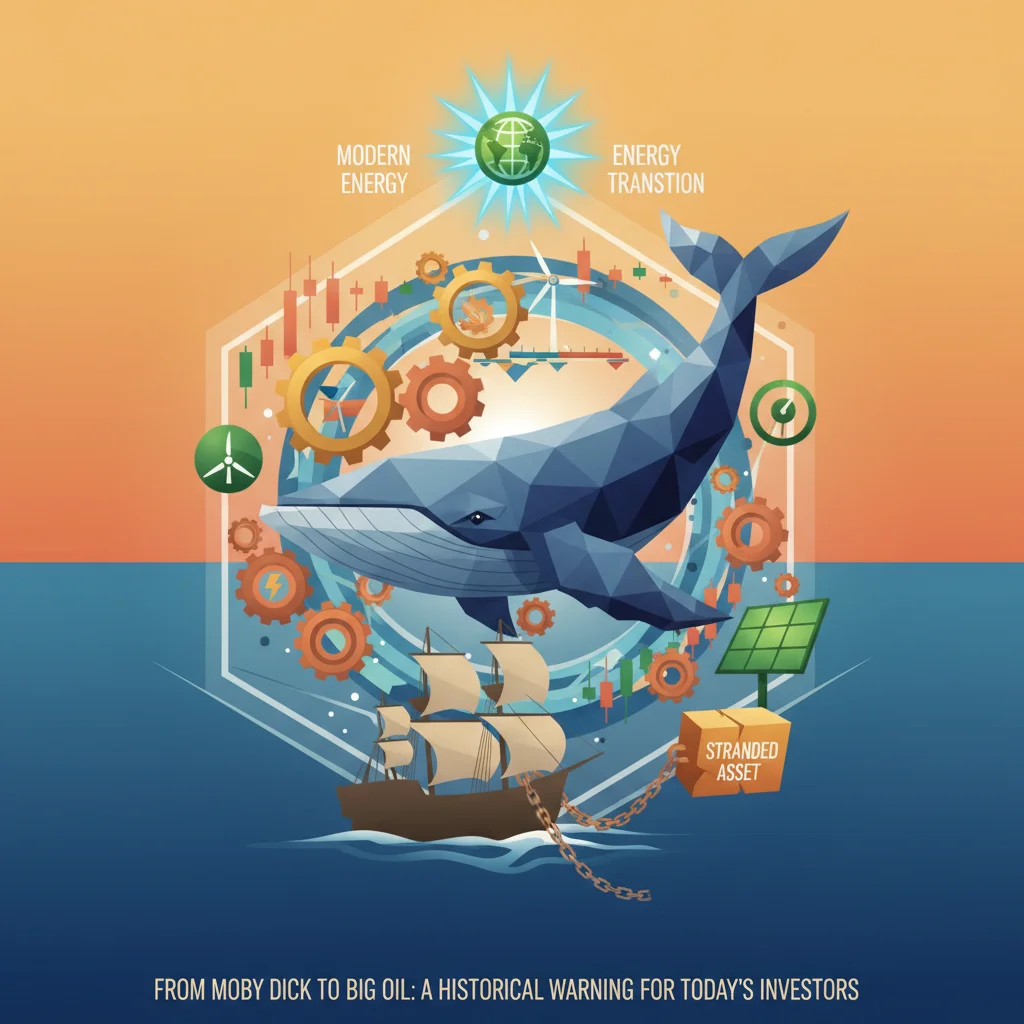

From Moby Dick to Big Oil: A Historical Warning for Today’s Investors

In the mid-19th century, towns like Hudson, New York, were bustling hubs of a global economic powerhouse. Their fortunes were not built on stocks or technology, but on the rendered fat of the planet’s largest mammals. The whale oil industry was the energy sector of its day, an indispensable commodity that lit homes, lubricated the gears of the Industrial Revolution, and generated immense wealth. Yet, within a few decades, this titan of the global economy collapsed, leaving behind a trail of worthless assets and a profound lesson for future generations.

A recent letter to the Financial Times by Thomas Paino of Hudson, a former whaling capital, draws a stark and compelling parallel between the catastrophe of the whale oil industry and the looming crisis facing today’s fossil fuel giants. This comparison is more than just a historical curiosity; it is a critical framework for understanding technological disruption, stranded assets, and the monumental shifts currently reshaping the world of finance, investing, and global economics.

Just as the mighty whaling ships once ruled the seas, the supermajors of oil and gas have dominated the last century. But as history shows, no empire is eternal, especially when faced with the relentless tide of innovation and changing societal demands. For investors, business leaders, and anyone with a stake in the future, the story of whale oil is a cautionary tale that echoes with urgent relevance today.

The Rise and Inevitable Fall of a Behemoth

To grasp the magnitude of the parallel, one must first appreciate the sheer dominance of the 19th-century whaling industry. At its zenith in the 1850s, the American whaling fleet numbered over 700 ships, a force that projected economic power across every ocean. Whale oil, particularly that from the sperm whale, was a premium product. It burned brighter and cleaner than any alternative, making it the fuel of choice for public and private lighting. Its value was so great that the industry was worth over $1.1 billion in today’s dollars at its peak, a staggering sum for the era.

This economic boom, however, was built on an unsustainable and environmentally catastrophic foundation. Whale populations were decimated, and the voyages required to hunt the dwindling survivors became longer, more dangerous, and less profitable. Yet, the industry’s downfall was not ultimately driven by resource scarcity or moral awakening, but by a force that every investor today fears and respects: disruptive technology.

In 1859, a discovery in Titusville, Pennsylvania, sealed the fate of the whaling industry. Edwin Drake successfully drilled the first commercial oil well, unleashing a flood of cheap, abundant petroleum. This raw material was soon refined into kerosene, a lighting oil that was vastly superior to its whale-derived predecessor. It was less expensive, more accessible, and didn’t require endangering a species. The market shift was swift and brutal. The value of whale oil plummeted. An industry that had once been a cornerstone of the American stock market and a symbol of prosperity found its entire business model obsolete.

The Architect's Portfolio: Rebuilding Your Financial Future with the Principles of Design

The Great Analogy: Fossil Fuels as the New Whale Oil

The parallels to our modern energy landscape are impossible to ignore. The fossil fuel industry is, in many ways, a scaled-up version of the whaling behemoth. It has powered global development for over a century, created unprecedented wealth, and woven itself into the very fabric of our geopolitical and financial systems. However, like the whalers of old, its business model is predicated on a finite resource with devastating environmental consequences.

The disruptors are also analogous. Kerosene was the 19th-century equivalent of today’s solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles. These modern technologies are rapidly descending the cost curve, driven by innovation, economies of scale, and supportive government policies. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has reported that global renewable capacity additions in 2023 increased by almost 50% from the previous year, reaching nearly 510 gigawatts (GW)—the fastest growth rate in two decades.

To better visualize this powerful historical comparison, consider the following breakdown:

| Feature | Whale Oil Industry (c. 1850s) | Fossil Fuel Industry (c. 2020s) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Lighting (whale oil lamps), Lubrication | Transportation, Electricity Generation, Industrial Processes |

| Economic Dominance | A leading global industry; powered early industrialization | The foundation of the modern global economy; multi-trillion dollar market |

| Environmental Impact | Devastation of global whale populations | Climate change, air and water pollution, habitat destruction |

| Key Disruptors | Petroleum (kerosene), natural gas, electricity | Solar, wind, battery storage, green hydrogen, EVs |

| Stranded Asset Risk | Ships, processing plants, and inventory became worthless | Oil and gas reserves, pipelines, refineries, power plants |

Navigating the Transition: A Modern Investor’s Playbook

For those involved in investing and finance, this historical parallel is not an academic exercise; it’s a strategic imperative. The concept of “stranded assets”—assets that suffer from unanticipated or premature write-downs or devaluations—has moved from the fringe to the mainstream of financial risk analysis. The Bank of England has warned that trillions of dollars in fossil fuel assets could be rendered worthless by a disorderly transition to a low-carbon economy. A 2021 study published in Nature estimated that nearly 60% of oil and gas reserves and 90% of coal must remain unextracted to meet a 1.5°C climate target.

This presents both a monumental risk and an unprecedented opportunity. The playbook for navigating this shift involves a two-pronged approach:

- De-risking from Incumbents: Investors must critically evaluate their exposure to companies heavily reliant on fossil fuel extraction. This doesn’t necessarily mean immediate divestment for all, but it does require a rigorous assessment of which companies are genuinely adapting their business models versus those who are simply managing a slow decline. The risk of holding the 21st-century equivalent of a whaling fleet is real and growing.

- Investing in the Disruption: The flip side of the risk coin is opportunity. The transition requires a staggering amount of capital. The IEA projects that annual clean energy investment worldwide will need to more than triple by 2030 to around $4 trillion to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. This capital will flow into renewable generation, grid modernization, energy storage solutions, electric vehicle infrastructure, and new technologies like green hydrogen. This is the new frontier for growth in the global economy.

Modern banking and finance are at the epicenter of this transition, creating new financial instruments, green bonds, and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) funds to channel capital toward a sustainable future. The field of financial technology is accelerating this by providing better data, risk modeling, and platforms for green investments.

UK Housing Correction: Decoding the £2,000 Price Drop and What It Means for Your Investments

Nuances and Complexities: Why This Time is Different (and Why it Isn’t)

Of course, no historical analogy is perfect. The scale and complexity of the modern fossil fuel economy dwarf that of the 19th-century whaling industry. The transition away from oil and gas is a far more intricate challenge for several reasons:

- Energy Density and Ubiquity: Fossil fuels are incredibly energy-dense and are integrated into nearly every aspect of modern life, from plastics to pharmaceuticals, in ways whale oil never was.

- Geopolitical Entanglement: The global balance of power, international relations, and the fortunes of entire nations are tied to oil and gas production and trade.

- Scale of Capital: The sheer value of the infrastructure—pipelines, refineries, power plants, and gas stations—is orders of magnitude greater than the capital tied up in the whaling industry.

Despite these differences, the core economic principle remains the same. When a superior, cheaper, and more sustainable technology emerges, the market will eventually shift. The inertia of the old system can delay the transition, but it cannot stop it. The fundamental laws of economics and innovation are as powerful today as they were in 1859.

The Price of Chaos: MI6's Dire Warning on Russia and Its Shockwaves Through the Global Economy

Conclusion: Heeding the Lessons of History

The story of Hudson, New York—from a thriving whaling capital to a modern town grappling with its industrial past—serves as a microcosm of the vast economic transformation that is once again upon us. The letter from Mr. Paino is a poignant reminder that industries built on the exploitation of a finite, natural resource are ultimately living on borrowed time.

For the modern investor, the choice is clear. One can remain invested in the whaling ships of our time, hoping for one last profitable voyage while ignoring the storm clouds of disruption on the horizon. Or, one can invest in the new fleet of technologies that will power the next century of economic prosperity. The history of whale oil teaches us that when the tide of innovation turns, it is far better to be building the new lighthouses than to be the last captain of a sinking ship.