The End of an Era or a New Financial Strategy? Why a Top Art Gallery is Closing its New York Doors

In a move that reverberated far beyond the polished floors of the art world, esteemed London-based gallerist Stephen Friedman has announced the closure of his New York gallery. While on the surface this may seem like a story for art aficionados, it is, at its core, a profound case study in modern business strategy, risk management, and the shifting tides of the global economy. For investors, finance professionals, and business leaders, Friedman’s “tough decision,” as he called it, offers critical insights into the challenges and opportunities facing high-value, high-overhead industries in a post-pandemic world.

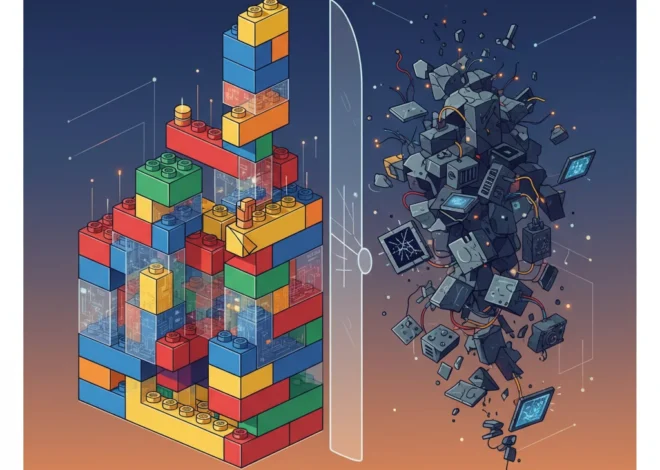

The closure of the Tribeca space, which only opened in 2022, is not a sign of failure but a strategic pivot. Friedman’s London headquarters remains a powerhouse, and his new focus is on “pursuing growth elsewhere,” according to a statement reported by the Financial Times. This single move encapsulates a broader trend: the decoupling of prestigious physical locations from business success. It forces us to ask a crucial question: In an age of digital connectivity and global capital, what is the true value of a brick-and-mortar footprint in one of the world’s most expensive cities?

The Unforgiving Economics of the Art World

To understand the gravity of Friedman’s decision, one must first appreciate the unique financial structure of the art gallery business. Unlike a typical retail operation, a gallery operates on a high-risk, high-reward model that bears more resemblance to venture capital than to a traditional storefront. The overhead is immense and fixed—exorbitant rent in prime locations, staffing, insurance, shipping, and marketing—while revenue is unpredictable, hinging on a handful of high-value transactions each year.

This model is particularly brutal in New York City, the undisputed epicenter of the global art market. The city’s dominance comes at a cost, with commercial real estate prices that can cripple even successful enterprises. For a mid-tier gallery like Stephen Friedman—highly respected but not in the same league as mega-galleries like Gagosian or David Zwirner—the financial calculus becomes a tightrope walk. The pressure to generate consistent, multi-million-dollar sales to simply cover costs is relentless. This decision highlights a fundamental principle of modern finance: capital must be deployed where it can generate the highest return, and sometimes that means cutting ties with assets—even prestigious ones—that are underperforming or excessively costly.

Art as an Asset: A Lesson in Portfolio Management

For many high-net-worth individuals and institutional clients, art is not merely decorative; it is a significant component of a diversified investment portfolio. It serves as a hedge against inflation and a store of value, often uncorrelated with the volatility of the traditional stock market. Viewed through this lens, Friedman’s strategic retreat from New York is a masterclass in portfolio management on a corporate scale.

He is effectively reallocating his capital away from a high-cost, high-maintenance asset (the New York gallery) to invest in more agile, potentially higher-yield opportunities. These might include expanding his presence at international art fairs, investing in digital platforms, or cultivating client relationships in emerging markets in Asia and the Middle East. This is akin to an investor selling a blue-chip stock with stagnant growth to invest in a more dynamic sector. The underlying principle is the same: optimize capital for growth and reduce exposure to unnecessary risk. The “growth elsewhere” Friedman mentions is not just geographical; it is a strategic shift in how the business of art is conducted.

To better understand this strategic pivot, let’s compare the traditional gallery model with the more agile approach Friedman appears to be adopting.

| Metric | Traditional Model (e.g., NY Physical Gallery) | Agile/Global Model (Friedman’s New Strategy) |

|---|---|---|

| Overhead Costs | Extremely high and fixed (rent, staff, utilities) | Lower and more variable (pop-ups, art fairs, digital) |

| Market Reach | Geographically limited to city foot traffic and reputation | Global, targeting clients in multiple regions directly |

| Client Engagement | Relies on physical exhibitions and local events | Diverse channels: private viewings, digital showrooms, global fairs |

| Operational Flexibility | Low; tied to a single, costly physical location | High; ability to pivot resources to emerging markets quickly |

| Risk Profile | Concentrated risk in one high-cost market’s economy | Diversified risk across multiple markets and channels |

The Role of Technology in a Changing Art Market

While the original article doesn’t delve into the technological aspect, it’s impossible to analyze this decision without considering the impact of financial technology and digital platforms. The art world, once notoriously slow to adopt new tech, has been forced to innovate. High-resolution online viewing rooms, virtual reality exhibitions, and sophisticated client relationship management systems now allow gallerists to engage with buyers across the globe without ever meeting them in person.

Furthermore, the rise of technologies like blockchain is addressing one of the biggest concerns for art investors: provenance and authenticity. By creating immutable digital ledgers for artworks, blockchain can enhance transparency and security in art trading, making high-value transactions less risky for international buyers. This technological infrastructure makes a physical gallery in every major city less of a necessity and more of a choice—a choice with a very clear price tag. Friedman’s decision suggests that, for his business, the cost of that choice outweighs the benefits. His gallery, which has championed artists like Yinka Shonibare and Kehinde Wiley (source), can now leverage its established brand and technology to serve its global clientele more efficiently.

Navigating the Tariff Tightrope: A CEO's Dilemma and What It Teaches Every Investor

Broader Implications for the Global Economy

Friedman’s exit from New York is a microcosm of larger economic shifts. It reflects the immense financial pressure on mid-sized businesses in “superstar” cities. It underscores the globalization of luxury markets, where the wealthiest clients are as likely to be in Dubai or Singapore as they are in New York. And it speaks to a post-pandemic recalibration of how and where business is done.

Companies in every sector are scrutinizing their real estate portfolios and asking the same hard questions. The glamour of a Park Avenue address or a City of London skyscraper is being weighed against the practicalities of a globalized, digitally-enabled workforce and client base. The field of economics is watching these trends closely, as they have major implications for urban development, commercial real estate markets, and the future of work.

For the art world, this may signal a period of decentralization. While New York will likely remain a critical hub, its absolute dominance may be challenged as galleries adopt more nimble, multi-polar strategies. For artists, it could mean more diverse opportunities for representation outside the traditional, hyper-competitive centers. For those investing in art, it serves as a reminder that the market is dynamic. The entities that facilitate the art trade are subject to the same financial pressures and strategic imperatives as any other business. As Friedman stated, despite the difficulty, he is “excited for the future,” a sentiment that suggests this is a calculated move towards a more sustainable and profitable business model (source).

The AI Paradox: How Technology Can Restore the Human Touch to Recruitment and Drive Economic Growth

Conclusion: A Strategic Retreat is a Forward March

The closure of Stephen Friedman’s New York gallery is far more than an art world headline. It is a compelling narrative about adaptation, financial prudence, and the courage to abandon a conventional status symbol in pursuit of a smarter, more resilient business strategy. It demonstrates a keen understanding of modern capital allocation, the power of a global brand, and the changing nature of client relationships in the digital age.

For anyone involved in investing, finance, or business leadership, the lesson is clear: success is no longer defined by your address, but by your agility. In a world of constant economic flux, the willingness to make tough decisions and pivot towards new models of growth is the most valuable asset of all.