The £40 Billion Question: Is the UK’s Proposed Student Levy a Smart Economic Move or a Costly Mistake?

The Human Cost of a Fiscal Calculation

For Manou, a dedicated student at the prestigious Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, the future hangs in the balance. Her dream of completing her degree in the UK is now clouded by uncertainty, not by academic challenges, but by a fiscal policy proposal. “I won’t be able to finish my degree if international fees go up,” she told the BBC, voicing a fear shared by thousands. The source of her anxiety is a proposed 6% government levy on international student fees, a move that, while seemingly minor on a spreadsheet, threatens to derail lives and, more broadly, undermine one of the UK’s most successful economic pillars.

While stories like Manou’s highlight the immediate human impact, they are also a canary in the coal mine for a much larger issue with profound implications for the UK economy, for investors, and for the nation’s standing on the global stage. This isn’t just about student affordability; it’s about the financial health of our universities, the stability of a major export industry, and the long-term competitiveness of the British workforce. For finance professionals and business leaders, the question is stark: is this policy a prudent fiscal adjustment or a strategic blunder that risks killing the golden goose?

Understanding the Economics of a Global Education Hub

To grasp the magnitude of what’s at stake, one must look beyond the university gates and into the national ledger. The UK’s higher education sector is not merely an academic pursuit; it is a powerhouse of economic activity. International students are at the very heart of this financial engine. They are not a drain on resources; they are a significant net benefit.

In a detailed 2023 analysis, the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) calculated that the net economic impact of just the 2021/22 cohort of international students was a staggering £37.4 billion. This figure accounts for their tuition fees, living expenses, and the knock-on effects on local businesses, balanced against the limited public services they consume. This contribution is not abstract; it translates into jobs, innovation, and tax revenue that supports public services for everyone.

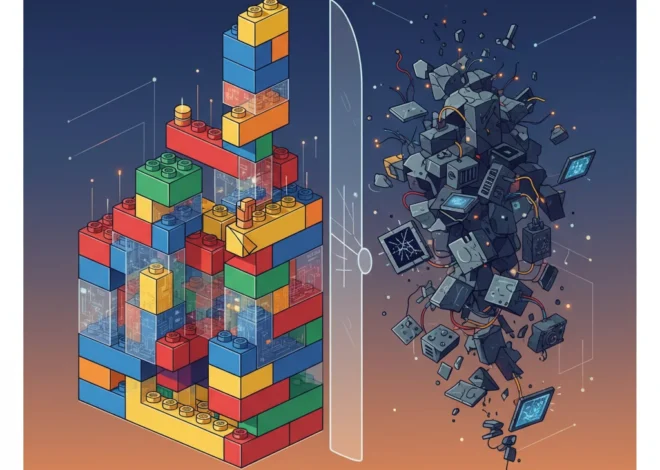

The financial architecture of UK universities has become increasingly reliant on this international income. For decades, tuition fees for domestic students have been capped and have not kept pace with inflation, creating a funding gap. International student fees, which are unregulated and often three to four times higher, are used to cross-subsidise domestic education, fund cutting-edge research, and maintain world-class facilities. A sudden shock to this revenue stream could destabilise the entire sector’s finance model.

The following table illustrates the immense economic contribution, breaking down the impact of the 2021/22 student intake:

| Metric | Value (for 2021/22 Cohort) |

|---|---|

| Total Economic Benefit to the UK | £41.9 billion |

| Total Costs to the UK | £4.4 billion |

| Net Economic Impact | £37.4 billion |

| Average Net Impact per EU Student | £71,000 |

| Average Net Impact per non-EU Student | £102,000 |

Source: Data adapted from the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) and Universities UK International report, “The costs and benefits of international higher education students to the UK economy.”

The Ripple Effect: From University Bonds to the Broader Stock Market

For investors and those in the financial sector, the stability of higher education is a key indicator. Universities are major employers, property owners, and borrowers. Many have issued bonds to fund capital projects, and their creditworthiness is directly linked to their financial outlook. A policy that threatens their primary source of surplus revenue introduces significant risk.

A decline in international student numbers could lead to:

- Downgraded Credit Ratings: A weaker financial forecast could lead agencies to downgrade university bonds, increasing their cost of borrowing and hampering future development.

- Pressure on Ancillary Markets: The multi-billion-pound purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) market is predicated on strong international demand. A downturn could impact property values and returns for institutional investors.

- Reduced R&D and Innovation: Less surplus cash means less internal funding for research and development, which ultimately fuels the UK’s tech and science sectors—areas critical for long-term growth and performance on the stock market.

This uncertainty sends a negative signal to the global investment community. It suggests a policy environment that is unpredictable and potentially hostile to one of its most successful international industries. In an era of fragile economic recovery, such self-inflicted wounds can have an outsized impact on investor confidence in “UK PLC.”

The Stealth Sell-Off: Unmasking the Hidden Corporate Debt Threat to Bitcoin's Price

A High-Stakes Game of Global Competition

The UK does not operate in a vacuum. The global market for higher education is intensely competitive. While the UK has historically punched above its weight due to the reputation of its institutions and the appeal of the English language, this advantage is not guaranteed. A 2023 report from the British Council highlighted that while the UK remains a top choice, prospective students are increasingly price-sensitive and concerned about visa and immigration policies (source). The proposed levy would be a direct, government-endorsed price hike, making the UK a harder sell.

This is not just about losing tuition fees. It’s about losing talent. The students who come to the UK are often the brightest from their home countries. Many stay on to work, start businesses, and contribute to the UK economy for years after graduation. They fill critical skills gaps in sectors like engineering, medicine, and financial technology. Discouraging this pipeline of talent is a long-term economic own goal.

The discussion around student mobility and credentials is also evolving. While still nascent in this sector, the principles of blockchain—decentralized, verifiable credentials—could one day make educational qualifications more portable and globally recognized. In such a future, the competition for talent will be even more fluid, and nations that create financial and administrative barriers will be left behind.

Can Technology Soften the Blow? The Role of Fintech and Banking

In the face of these rising costs, could technology offer a solution? The fintech sector is already innovating to ease the financial burdens on international students. Companies are creating platforms that offer more competitive currency exchange rates for fee payments, bypassing the high fees often charged by traditional banking institutions. New lending models are emerging that use alternative data to provide loans to students without a UK credit history.

These financial technology solutions are valuable, but they are a patch, not a cure. They can help a student manage a 2-3% cost saving on a transaction, but they cannot absorb a 6% systemic levy imposed by a government. They can ease the friction in the system, but they cannot fix a fundamentally uncompetitive price point. The core issue remains one of policy, not a lack of innovative payment or trading tools.

The Hidden Costs of Clicks: Why a UK Probe into Deceptive Online Pricing is a Red Flag for Investors

Conclusion: A Crossroads for a Critical UK Asset

The story of Manou at Trinity Laban is a microcosm of a critical national crossroads. The proposed 6% levy on international student fees, framed as a simple revenue-raising measure, is in fact a high-stakes gamble with one of the UK’s most valuable and globally respected assets. It pits a short-term fiscal gain against the long-term economic prosperity, innovation, and global influence that a vibrant international education sector provides.

For investors, business leaders, and financial professionals, the situation warrants close attention. It is a test of the government’s understanding of modern economics and its commitment to fostering a pro-growth environment. By making the UK a more expensive and less certain destination, we risk not only the dreams of individual students but also the financial stability of our world-class universities and a significant source of national income. The £40 billion question remains: is the price of this policy one the UK can truly afford to pay?