Data-Driven Decisions or Digital Overreach? The Lloyds Banking Controversy and the Future of Corporate Ethics

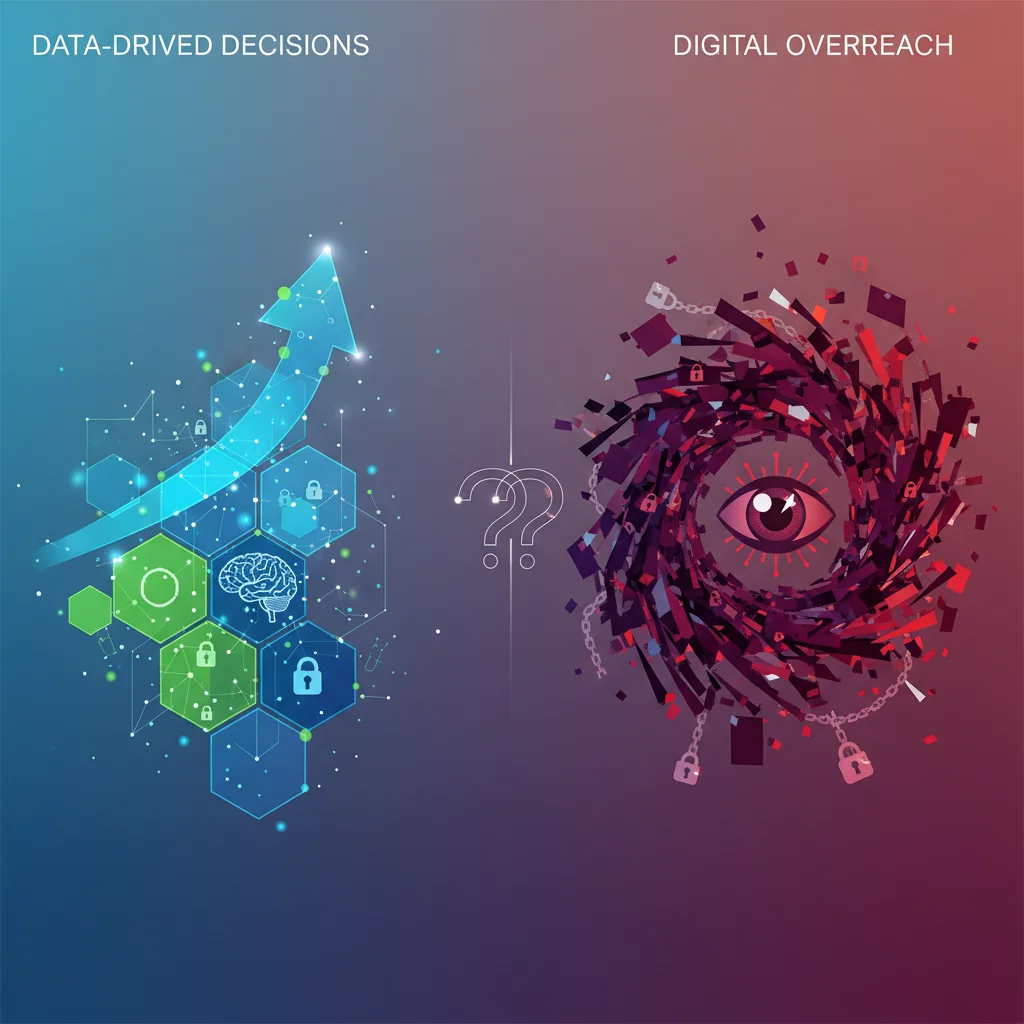

In the relentless pursuit of data-driven decision-making, where does a corporation draw the line? At what point does insightful analysis cross into intrusive surveillance, particularly when it involves the very people who constitute the organization? This question has been thrust into the spotlight by a recent revelation at Lloyds Banking Group, one of the UK’s largest financial institutions. The bank confirmed its use of anonymised staff account data—analysing spending habits, saving rates, and salary trends—to inform its position during pay negotiations. This move, described as “concerning” by the employee union Accord, serves as a critical case study for the modern economy, forcing us to confront the profound ethical questions at the intersection of financial technology, corporate governance, and employee trust.

According to a report from the BBC, Lloyds utilised this aggregated data to understand the financial pressures its workforce was facing amidst a cost-of-living crisis. The bank’s stated intention was to formulate a “fair and balanced” pay offer. On the surface, this might seem like a progressive, empathetic approach—a company leveraging its unique analytical capabilities to better care for its employees. However, the context is everything. When this data is used not just for general insight but to specifically prepare for salary negotiations, the dynamic shifts from paternalistic care to strategic leverage, raising alarms for employees, regulators, and investors alike.

Decoding the Data: What Lloyds Analysed and Why It Matters

The core of the controversy lies in the type of data used and the purpose for which it was deployed. Lloyds looked at three key areas of its employees’ financial lives:

- Spending Habits: Analysing where and how employees spend their money to gauge the impact of inflation on daily life.

- Saving Rates: Assessing the capacity for employees to save money, indicating their level of financial resilience.

- Salary Increases: Tracking the trajectory of pay within the organisation to benchmark offers.

Lloyds has been adamant that all data was anonymised and aggregated, meaning individual employees could not be identified. From a purely technical and legal standpoint, this may satisfy data protection regulations like GDPR. However, this technical compliance sidesteps a much deeper ethical issue. The very knowledge that an employer is scrutinising the collective financial behaviour of its staff can create a chilling effect. Employees may feel that their personal financial lives, albeit anonymised, are being used as a bargaining chip against them. It transforms the employer-employee relationship from one of mutual trust to one of surveillance, fundamentally altering the power balance in negotiations.

This incident is not happening in a vacuum. It is part of a much larger trend in the world of finance and human resources, often referred to as “People Analytics.” As a study on the ethics of HR analytics points out, while data can help eliminate bias and improve decision-making, it also “poses a risk to employee privacy and autonomy” if not governed by a strong ethical framework (source). The unique position of a bank, which acts as both employer and financial custodian, makes this issue exponentially more complex and sensitive.

The Double-Edged Sword of Financial Technology in HR

The rise of fintech has equipped financial institutions with unprecedented tools for data analysis. These same tools, typically used for risk assessment, fraud detection, and understanding customer behaviour, are now being turned inward. The Lloyds case demonstrates how a bank’s core competency—analysing financial data—can be repurposed for internal functions like human resources. This presents both a powerful opportunity and a significant peril.

To better understand this dichotomy, consider the potential benefits and risks of using employee financial data within a corporate setting.

| Potential Benefits (The ‘Utopia’ View) | Potential Risks (The ‘Dystopia’ View) |

|---|---|

| More Empathetic Policies: Data can reveal systemic issues, like the impact of inflation, allowing companies to proactively adjust pay or benefits. | Erosion of Trust: Employees may feel constantly monitored, leading to a culture of suspicion and reduced psychological safety. |

| Objective Decision-Making: Aggregated data can provide a more objective basis for compensation strategies, potentially reducing individual biases. | Asymmetric Power Dynamic: The employer gains a significant information advantage in negotiations, undermining the principles of good-faith bargaining. |

| Targeted Wellness Programs: Insights could help design financial wellness and support programs that address genuine employee needs. | The “Slippery Slope”: If acceptable for pay talks, could this data be used for promotions, performance reviews, or even redundancy selections? |

| Enhanced Economic Modelling: Understanding workforce financial health helps the company model its own resilience and impact on the broader economy. | Anonymity Fallacy: While technically anonymised, sophisticated data analysis can sometimes lead to de-anonymisation, posing a severe privacy breach. |

Broader Implications for Investing, Governance, and the Economy

The ripples from this single case extend far beyond Lloyds’ headquarters, touching upon key aspects of the modern financial landscape.

1. A New Frontier for ESG Investing

For the investing community, this is a landmark moment for the “S” in ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance). For years, the “Social” component has often been the most difficult to quantify. Incidents like this provide a concrete metric for evaluating a company’s approach to employee relations and data ethics. A 2022 report by MSCI highlighted that issues related to labour management and data privacy are increasingly material financial risks for corporations (source). Investors will, and should, start asking pointed questions: What is your policy on using employee data? How do you ensure ethical oversight of your analytics programs? A failure to provide clear, reassuring answers could impact a company’s valuation and its position on the stock market.

2. The Future of Labor Negotiations

Traditionally, pay negotiations have been based on market rates, company performance, and the collective voice of a union. The introduction of granular, private employee financial data fundamentally disrupts this model. It creates an information asymmetry that unions are ill-equipped to counter. This could either weaken the position of unions or force them to become more sophisticated in their own data strategies, leading to a new, more complex era of industrial relations. The balance of power in our economy is subtly but significantly being altered by who controls the data.

3. The Regulatory Horizon

While Lloyds’ actions may exist in a legal grey area today, regulators will be paying close attention. The spirit of regulations like GDPR is to give individuals control over their personal data. The use of “anonymised” data is often a loophole. As European data protection authorities have clarified, data is only truly anonymous if re-identification is impossible, a standard that is increasingly difficult to meet (source). We can expect future legislation to address the ethics of aggregated data analysis, especially in sensitive contexts like employment.

Looking further ahead, some technologists propose that privacy-preserving technologies like blockchain could one day offer a solution, allowing for verifiable analysis without revealing the underlying data. However, such solutions are far from mainstream, leaving us to navigate the current ethical minefield with policy and principles.

A Call for a New Corporate Data Ethos

The Lloyds case is a canary in the coal mine, signalling a future where every aspect of our lives, including our private financial behaviour, can become a data point in a corporate algorithm. To prevent a slide into a culture of digital distrust, a new framework is needed.

- For Business Leaders: The priority must be to establish transparent and robust data governance policies. These policies should be co-created with employees, not imposed upon them. The guiding principle should be “trust through transparency.” Any use of employee data must be clearly communicated, ethically vetted, and have an opt-out mechanism where possible.

- For Investors: It’s time to deepen the scrutiny of corporate culture as a core component of risk analysis. Ask management tough questions about their People Analytics strategies. Reward companies that demonstrate a genuine commitment to ethical data stewardship, as they are likely to be more resilient and sustainable in the long run.

- For Finance Professionals: The power of modern banking and financial technology comes with an immense responsibility. Professionals in the field must champion an ethical code of conduct for data use, recognising that maintaining public and employee trust is the ultimate currency.

Primark at a Crossroads: Why a Potential Spin-Off Signals a New Era for Retail Investing

Conclusion: Beyond the Numbers

The controversy at Lloyds Banking Group is more than a dispute over pay negotiations; it is a defining moment in the digital age. It forces a reckoning with the idea that just because we can analyse something does not mean we should. The relentless drive for data-driven efficiency in our economy cannot come at the cost of human dignity, privacy, and trust.

As corporations, investors, and employees, we stand at a crossroads. One path leads to a future of opaque algorithms and asymmetric power, where employees are reduced to predictable data sets. The other leads to a more enlightened model of capitalism, where technology serves to enhance transparency and build stronger, more trusting relationships. The choices made today, in the boardrooms of companies like Lloyds, will determine which future we build.