Beyond GDP: The Hidden Metric Revealing the UK’s True Economic Struggle

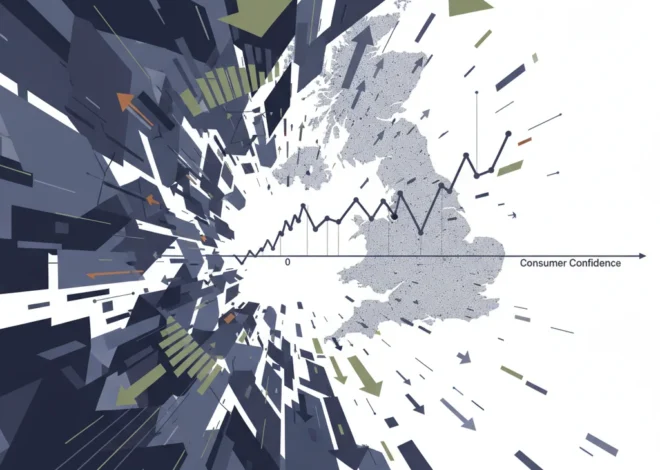

On the surface, the UK economy appears to be treading water, even showing modest signs of growth. Headline figures for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per head, the most commonly cited barometer of a nation’s economic health, suggest a recovery, however sluggish. Yet, a palpable “feelbad factor” persists across the country. Households feel squeezed, public services are strained, and a sense of economic stagnation is widespread. Why this stark disconnect between official data and lived experience?

The answer may lie in the very metric we use to measure success. According to Martin Weale, a professor at King’s College London and a former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, our reliance on GDP is masking a more troubling reality. A more insightful, albeit less discussed, indicator—Net National Income (NNI) per head—paints a far bleaker picture. It suggests that while the UK is producing more, it isn’t actually getting richer. In essence, the nation is running faster and faster just to stand still.

This article delves into this crucial distinction, exploring why NNI is a superior measure of our economic well-being and what its decline means for investors, business leaders, and every citizen in the UK.

The Great Deception: Why GDP Fails Us

For decades, GDP has been the undisputed king of economic indicators. In the world of finance and economics, its quarterly release is a major event, capable of moving the stock market and shaping government policy. GDP measures the total value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders over a specific period. It’s a measure of output, of economic “churn.”

However, its limitations are profound. GDP is like measuring a company’s total revenue without considering its costs. It tells you how much activity is happening, but not whether that activity is creating sustainable wealth. It famously includes spending on disaster recovery and counts building a new prison as a positive contribution, yet it ignores the value of unpaid care work or the depletion of natural resources.

Most critically for the UK’s current situation, GDP fails to account for a crucial expense: the depreciation of our national capital stock. This is the “wear and tear” on everything that helps us produce, from factory machinery and office buildings to roads, railways, and even software. Just as you must service your car to keep it running, a country must invest simply to maintain its existing productive capacity. GDP measures the new car rolling off the assembly line but ignores the cost of the aging fleet it’s destined to join.

A Truer Measure: Understanding Net National Income (NNI)

This is where Net National Income (NNI) provides a more honest assessment. NNI adjusts the headline GDP figure to give a clearer picture of the income actually available to a nation’s citizens. The calculation is a simple, yet powerful, refinement:

- Start with GDP: The total output of the economy.

- Subtract Capital Depreciation: This is the crucial step. By deducting the value of capital that has been “used up” or worn out, we move from a “gross” to a “net” figure. This gives us Net Domestic Product (NDP).

- Add Net Income from Abroad: This accounts for income earned by UK residents from overseas investments minus income paid to foreign residents on their UK investments.

The result, NNI, represents the real income the country has at its disposal for consumption and new investment after maintaining its existing capital base. It’s the economic equivalent of your take-home pay after you’ve set aside money for essential repairs on your home and car.

The Verdict on the UK Economy: Why Scrapping Jury Trials Could Rattle Global Investors

The Shocking Divergence in the UK

The theoretical difference between GDP and NNI has become a stark reality in the post-pandemic UK economy. As Martin Weale highlights, the data reveals a dramatic and worrying split. The following table illustrates the divergence in growth between these two key metrics since the end of 2019, a common baseline for pre-pandemic comparison.

| Economic Indicator | Growth Since Q4 2019 | What It Represents |

|---|---|---|

| GDP per Head | +4.5% | The total output produced per person in the UK. |

| Net National Income (NNI) per Head | -1.2% | The actual income available per person after maintaining the nation’s assets. |

Source: Data referenced from analysis by Martin Weale, based on ONS statistics.

This is the statistical heart of Britain’s plight. While the nation is producing 4.5% more per person, a sharp rise in capital depreciation means we are effectively 1.2% poorer in terms of disposable national income (source). A growing slice of our economic pie is being used not to add new toppings, but simply to repair the cracks in the baking dish. This explains why tax revenues feel strained and why funding for public services is a constant battle, even when GDP figures suggest the country should be better off.

Implications for a Stagnant Nation

This NNI-driven perspective has profound implications for every corner of the UK economy, from personal finance to corporate strategy and government policy.

For Investors and the Stock Market

For those involved in trading and investing, looking past headline GDP is now essential. A declining NNI suggests a weaker underlying consumer base and a more challenging environment for domestic-facing companies. It signals that corporate profits may be increasingly diverted towards capital replacement rather than expansion or shareholder returns. Investors should scrutinize company balance sheets for rising depreciation charges and capital expenditure needs. This environment may favor sectors focused on efficiency, automation, and maintenance—the very tools needed to combat the effects of a depreciating capital base. The rise of financial technology, or fintech, solutions that help businesses optimize assets and manage costs becomes even more critical.

Solving the Financial Puzzle: A Guide to Navigating Today's Complex Economy

For Business Leaders

Business leaders must confront the reality that a significant portion of their revenue may be required just to maintain current operations. The era of “sweating the assets” may be ending, replaced by a period of necessary, and costly, reinvestment. This reality should spur a renewed focus on genuine productivity gains. It’s not enough to simply produce more; businesses must produce more efficiently. This means embracing new technologies, streamlining operations, and making strategic investments in modern, durable capital that depreciates more slowly or delivers a much higher return. According to the Office for National Statistics, UK labour productivity has remained sluggish, a problem exacerbated by an aging capital stock.

For Policymakers and the Public

The most significant implications are for the government. Policies aimed solely at boosting GDP—such as temporary consumption-led stimulus—may be counterproductive if they don’t also encourage long-term investment. The focus must shift to policies that increase the national net worth. This includes creating a stable environment for private investment, funding public infrastructure projects wisely, and incentivizing the adoption of cutting-edge technology. For the public, this data confirms that the feeling of being economically squeezed is real. It reinforces the need to demand a more sophisticated conversation about the economy from our leaders—one that prioritizes sustainable prosperity over fleeting output.

The Future of Measurement and Wealth Creation

The UK’s predicament highlights a global need to move beyond GDP. International bodies like the OECD are already championing broader frameworks that include measures of well-being and sustainability. As our economies become more complex and technology-driven, our metrics must evolve.

Advanced data analytics and financial technology can help us track capital depreciation and national wealth more accurately. Some futurists even speculate that technologies like blockchain could one day provide immutable, transparent ledgers of national assets, offering a real-time view of our collective balance sheet. This shift aligns with the broader movement in the banking and finance world towards ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria, which recognizes that true value extends beyond a single financial number.

Ultimately, what gets measured gets managed. By shifting our focus from the gross to the net, from mere output to sustainable income, we can begin to have a more honest conversation about the UK’s economic challenges. The first step to solving a problem is to measure it correctly. The divergence between GDP and NNI is a clear signal that it’s time to change our ruler.

Beyond the Headlines: Decoding the Putin-Trump Envoy Meeting and Its Shockwaves for Global Finance

Conclusion: From Running in Place to Moving Forward

The story told by Net National Income is a sobering one. It reveals a UK economy working harder but not getting richer, with an ever-larger share of its efforts dedicated to patching up an aging foundation. This is the statistical reality behind the pervasive “feelbad factor.”

Ignoring this metric is no longer an option. For investors seeking real returns, business leaders aiming for sustainable growth, and a government that hopes to deliver genuine prosperity, the message is clear. We must look beyond the illusion of GDP and focus on the hard, unglamorous work of rebuilding our national capital stock and boosting our net national income. Only then can the UK economy stop running in place and finally start moving forward.