The Hidden Flaw in Our Economy: What the UK Doctors’ Strike Reveals About Our Financial Reality

The sight of junior doctors on picket lines has become a recurring and potent symbol of the UK’s economic pressures. While the headlines often focus on the immediate dispute over pay and working conditions, a deeper, more systemic issue is at play—one with profound implications for finance, investing, and the very stability of our economy. The British Medical Association (BMA) has repeatedly claimed that junior doctors have faced a real-terms pay cut of over 35% since 2008. Yet, if you look at the UK’s headline inflation figures, that number seems difficult to reconcile. This glaring discrepancy isn’t just a negotiating tactic; it’s a warning sign.

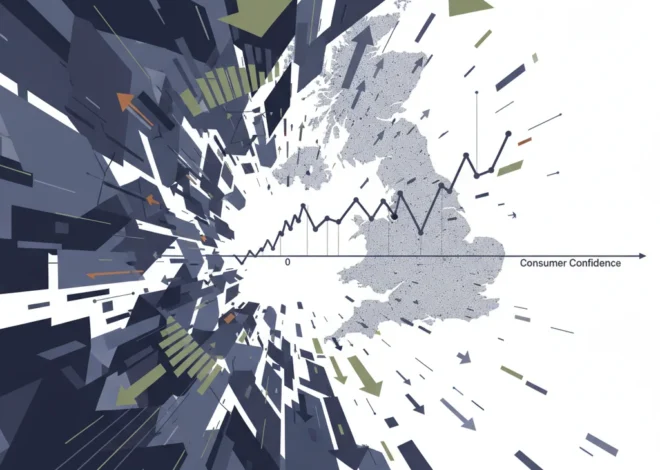

A recent letter to the Financial Times from Paul Allin, an Honorary Officer for Public Statistics at The Royal Statistical Society, brings this issue into sharp focus. He argues that the doctors’ strike is a powerful case study demonstrating why the UK’s primary measure of the cost of living—the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH)—is failing to capture the true financial pain experienced by millions. This isn’t merely an academic debate for statisticians. When the primary tool we use to measure our economic health is flawed, it leads to flawed decisions everywhere, from the Bank of England’s interest rate policies to corporate investment strategies and your personal finance planning.

In this analysis, we will dissect why our official inflation compass may be pointing in the wrong direction, explore the cascading consequences for the stock market and the broader economy, and consider what a more accurate measure of our financial reality might look like.

Decoding the Alphabet Soup: Why Not All Inflation Measures Are Created Equal

To understand the heart of the problem, we first need to navigate the often-confusing world of inflation indices. For decades, the UK has used several different metrics to track the rising cost of goods and services. The three most prominent are the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), the Retail Prices Index (RPI), and the current official favourite, CPIH.

Each index measures a slightly different “basket of goods” and uses different methodologies, leading to significant variations in their results. Understanding these differences is crucial for anyone involved in finance, trading, or economic forecasting.

Here is a simplified breakdown of the key differences between these major UK inflation indices:

| Index | Key Features | Common Uses | Main Weakness/Criticism |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPI (Retail Prices Index) | The oldest measure. Includes mortgage interest payments and council tax. Uses a different calculation formula (Carli). | Historically used for index-linked bonds (gilts), student loans, and some pension uplifts. | The Office for National Statistics (ONS) deems its formula flawed, stating it has an upward bias. It is being phased out. |

| CPI (Consumer Prices Index) | Excludes most housing costs for owner-occupiers. Aligned with European standards. Uses a geometric mean for calculations. | The Bank of England’s official target for monetary policy (currently 2%). Used for uprating state benefits and pensions. | By excluding owner-occupier housing costs, it misses a major expense for a large portion of the population. |

| CPIH (CPI including Owner Occupiers’ Housing Costs) | The ONS’s lead measure since 2017. It’s CPI plus a measure for housing costs for homeowners. | Intended to be the most comprehensive measure for understanding consumer price inflation. | The methodology for calculating housing costs (rental equivalence) is highly controversial and doesn’t reflect actual mortgage costs. |

The move to CPIH was intended to create a more comprehensive picture by including housing costs, a glaring omission from CPI. However, as Paul Allin points out, the *way* it includes them is the source of the current controversy.

The “Rental Equivalence” Illusion: Where the Data Diverges from Reality

The core of the problem with CPIH lies in a concept called “rental equivalence.” Instead of measuring the actual costs of homeownership—such as soaring mortgage interest payments, insurance, and maintenance—the ONS estimates what a homeowner would pay to rent their own home. This is known as “imputed rent.”

In a stable interest rate environment, this might be a reasonable, if imperfect, proxy. But in the current economy, it creates a massive distortion. Over the past two years, the Bank of England has raised interest rates from 0.1% to 5.25% in an effort to control inflation. This has caused mortgage payments for millions of households to skyrocket. Yet, because CPIH uses rental equivalence, this dramatic and painful increase in real-world costs is almost entirely absent from the headline inflation figure.

The rental market, while also experiencing inflation, has not moved in lockstep with mortgage costs. The result is an official inflation figure that significantly understates the cost-of-living crisis for homeowners, which includes a large number of the striking doctors and other professionals. This is why a union can claim a 35% real-terms pay erosion while the government, pointing to official CPIH data, can counter that the demand is unreasonable. They are both looking at the same economy through two completely different lenses.

The Billion-Pound Time Glitch: Why a One-Hour Mistake Toppled the UK's Top Economic Watchdog

The Ripple Effect: How Flawed Data Distorts the Entire Financial System

This statistical discrepancy is not a trivial matter. It has far-reaching consequences that ripple through every corner of the financial world.

- Monetary Policy Errors: The Bank of England sets its base rate with the primary goal of keeping CPI at 2%. But if both CPI and CPIH are understating the true inflationary pressures felt by households, the Bank may be making policy decisions based on incomplete or misleading information. This could lead it to undertighten (letting real-world inflation run rampant) or overtighten (crushing the economy to fight a statistical ghost), both of which are perilous for the banking sector and overall economic stability.

- Investment and Trading Miscalculations: For investors, the “real return” on an asset (the nominal return minus inflation) is a critical metric. If you believe inflation is 3% based on CPIH, a 5% return on a corporate bond looks attractive. But if the “true” inflation impacting your costs is closer to 7%, you are actually losing purchasing power. This mispricing of risk can lead to significant capital misallocation across the stock market, bond markets, and other asset classes.

- Corporate Strategy and Labour Unrest: The doctors’ strike is the canary in the coal mine. When official data fails to reflect lived experience, it erodes trust and fuels labour disputes across all sectors. Businesses that use CPIH to benchmark salary increases will find themselves with a demoralized and disgruntled workforce, impacting productivity and retention.

- The Fintech Opportunity: This credibility gap in official statistics creates an opportunity for financial technology. Innovative fintech companies can leverage alternative data sources—such as real-time transaction data, property listings, and sentiment analysis—to build more accurate, dynamic, and even personalized cost-of-living indices. This could become an invaluable tool for investors, businesses, and consumers seeking a clearer picture of the economy.

The Search for a Better Compass

If CPIH is flawed, what is the alternative? The ONS is not blind to these criticisms. In fact, they are already developing a different measure known as the Household Costs Index (HCI). According to a briefing from the House of Commons Library, the HCI is designed to more closely reflect the actual change in costs faced by households.

Crucially, the HCI includes things like mortgage interest payments, stamp duty, and other direct costs of homeownership. Unsurprisingly, in the current high-interest-rate environment, the HCI shows a significantly higher rate of inflation than CPI or CPIH. The challenge, however, is that creating a single, perfect index is impossible. The spending patterns of a young renter in a city are vastly different from those of a retired homeowner in the countryside. An ideal future might involve a primary headline index for macroeconomic policy, supplemented by a dashboard of other indices—like the HCI—that provide a more granular view for different demographic groups.

Solving the Market's Matrix: Why Investing is Like the Ultimate Crossword Puzzle

Actionable Takeaways for Investors and Business Leaders

Navigating an economy where official data may be misleading requires a more sophisticated approach. Simply accepting the headline inflation number is no longer sufficient.

- For Investors: Dig deeper than the headline figure. Analyze the components of the inflation reports to see where the pressures are coming from (e.g., services vs. goods, energy vs. food). Consider diversifying portfolios with assets that offer a better hedge against the “real-world” inflation not captured by CPIH, such as inflation-linked government bonds, infrastructure, and certain commodity-exposed equities. Be skeptical of “real return” calculations that rely solely on one flawed index.

- For Business Leaders: When conducting annual salary reviews or negotiating with unions, be prepared to look beyond CPIH. Acknowledge the real pressures your employees are facing, particularly regarding housing costs. Using a wider set of data, including the HCI or even internal surveys, can lead to more productive negotiations and help retain top talent.

- For Finance Professionals: Stress-test your financial models using different inflation scenarios. If your models for everything from company valuation to risk management are hard-coded to CPI, you may be underestimating your risk exposure. The world of economics is becoming more complex, and a multi-index approach is becoming essential for robust financial analysis.

Rethinking the Mansion Tax: A Blueprint for a Smarter, Fairer Property Levy

Conclusion: Beyond the Picket Line

The UK doctors’ strike is more than a dispute over pay; it is a powerful critique of our economic measurement tools. It highlights a growing chasm between official statistics and the lived financial reality of millions. The letter from The Royal Statistical Society is a call to action that we should all heed.

For the economy to function effectively, there must be a shared, trusted understanding of the challenges we face. When the compass we use to navigate is broken, we risk making policy and investment decisions that drive us further off course. Addressing the flaws in our cost-of-living indices is not just a technical exercise for economists; it is a fundamental step toward rebuilding trust, fostering fair negotiations, and making smarter decisions for a healthier and more prosperous financial future.